How to Feast for Your Eyes

Emily Chew has a vision to reduce the risk of eye disease by filling gaps in nutrition.

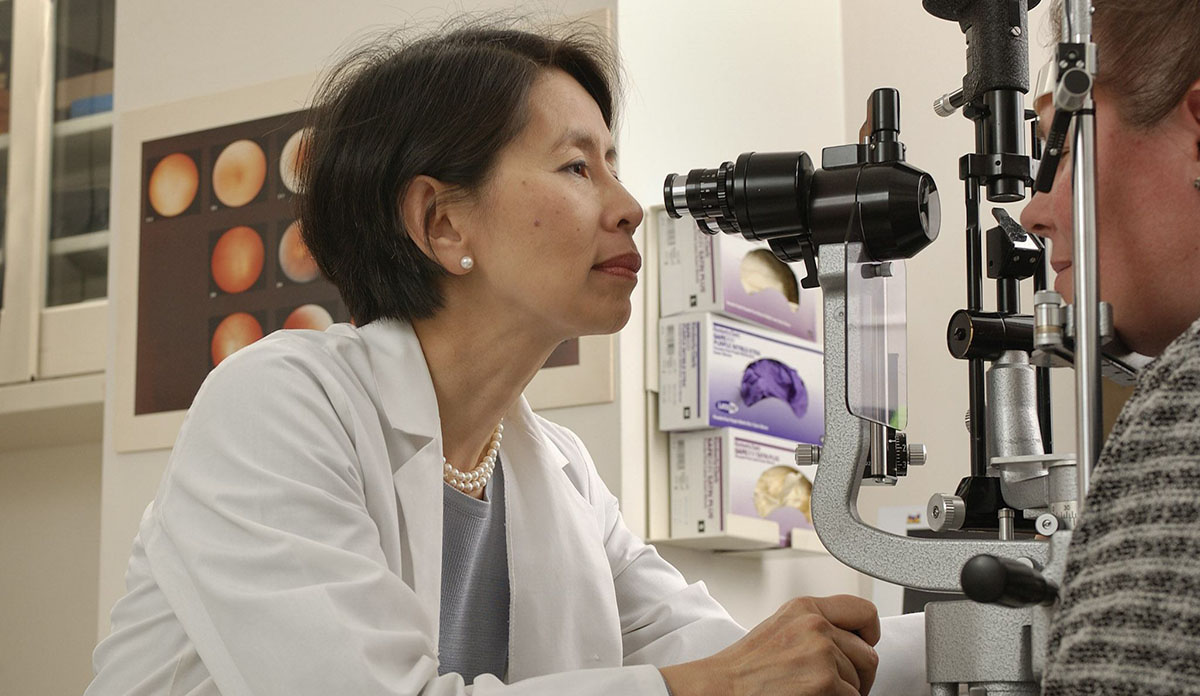

Dr. Emily Chew

It is often said that you are what you eat, but according to Dr. Emily Chew, you also see how you eat. Whether it’s building strong bones, fueling muscles, or regulating gut function, our bodies need the proper nutrients to stay healthy — and our visual system is no exception.

As the director of the Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications and the deputy clinical director of NIH’s National Eye Institute (NEI), Dr. Chew focuses on the retina, the layer of tissue lining the back inside wall of the eye that converts incoming light into electrical signals that the brain interprets to produce our sense of sight. To develop normally and work well, the retina must have the right ingredients.

“Our retinas need high concentrations of nutrients that we can get from our diet,” says Dr. Chew.

The idea that what we eat affects our eyes is far from new. The ancient Greeks, for example, took to eating raw beef liver to treat night blindness. Similarly, carrots and bilberries — a close cousin to blueberries — gained a reputation for improving night vision during World War II when rumors spread that British Royal Air Force pilots increased their success in night bombing missions after eating a diet rich in both foods.

Unfortunately, no amounts of liver, carrots, or bilberries will give you owl-like night vision. Nevertheless, all three foods are abundant in vitamin A, which is essential for overall eye health, as seen in children with poor vision and a vitamin A deficiency whose sight improves with daily supplements.

Dr. Chew suspects that other eye-related conditions could also be the result of nutrient deficits in people’s diets. She is taking a closer look at how these nutritional gaps contribute to vision loss, setting her sights on slowing the progression of retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

“Patients with AMD usually have problems reading or adjusting their vision in dimly lit conditions, or they’ll have warped vision, like seeing crooked telephone poles or window frames,” says Dr. Chew. These distortions result from deterioration in the center part of the retina, called the macula, and can eventually rob patients of clear central vision.

AMD is an eye disease that causes blurriness or spots in the center of your vision. Video courtesy of the National Eye Institute (NEI).

In a long-term study of nearly 4,000 people with AMD between the ages of 55 and 80, Dr. Chew and her collaborators tested how a dietary supplement affected the disease’s advancement. The supplement contained antioxidants in the form of vitamins C and E along with minerals like zinc and copper and was called AREDS after the name of the study — Age-Related Eye Disease Study. After five years, the researchers found that people with early-stage AMD who took AREDS had a 25 percent lower risk of developing advanced AMD.

“It turned out to be a secondary prevention, in that you have to be at a certain early stage of the disease in order to benefit from the supplement,” Dr. Chew explains.

Macular degeneration is characterized by the appearance of small yellow or white deposits, called drusen, on the retina. These deposits can accumulate and impair clear central vision.

From close analysis of participants’ diets over the course of the study, the researchers also learned that people who ate more leafy green vegetables and fish tended to have a lower risk of developing advanced AMD. Encouraged by this data, Dr. Chew and her team organized a second AREDS study testing whether adding lutein and zeaxanthin — compounds found in the leaves of collard greens, spinach, and kale — along with the omega-3 fatty acids of oily fish such as salmon, could further slow the course of AMD.

The researchers concluded that omega-3s didn’t have a significant effect, but lutein and zeaxanthin were somewhat effective, especially as substitutes for beta-carotene, another plant-derived compound used in the original AREDS supplement that was found to increase the risk of cancer by independent studies. The AREDS2 supplement was approximately 20 percent more beneficial for reducing progression to advanced AMD compared to the original formula that contained beta-carotene.

AREDS2 is now available in stores, but Dr. Chew emphasizes that people should not take it unless an eye specialist has spotted the firsts signs of disease in their retinas. Instead, she recommends focusing on getting the same nutrients directly from food. Trends in both AREDS studies suggest that a Mediterranean diet, which includes lots of vegetables, whole grains, fish, and olive oil, is better at staving off AMD than the supplement alone.

“This is just observational data — but it’s compelling that people who eat well avert the development of disease,” says Dr. Chew.

Dr. Chew recommends a Mediterranean diet consisting of fish, olive oil, vegetables, and grains to lower the risk of AMD.

Aside from nutritional insights, the AREDS studies are also spurring new directions in the study of macular degeneration that take advantage of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. Her team is currently working with Zhiyong Lu, Ph.D., from NIH’s National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) to process the trove of retinal images collected from participants over the course of the studies. Together, they are attempting to create a computer algorithm that can help detect AMD and predict its progression. The project involves training a computer using retinal images from people who went on to develop advanced AMD and others from people who didn’t in the hopes that the computer can learn to use a baseline scan of the retina to identify patients who are more likely to develop severe AMD.

“It’s quite remarkable what it can do and, so far, it’s pretty darn accurate,” says Dr. Chew. In the future, she intends to include other relevant factors in the AI-based assessments, such as age, genetics, behavioral habits like smoking, and health histories, which will help paint a more comprehensive picture detailing an individual’s risk of developing AMD.

Her foray into AI represents one of the many collaborations Dr. Chew has had in her 30 years at NIH. She recognizes that fostering such interdisciplinary collaborations is a testament to the sense of camaraderie in the IRP.

“Working so closely with collaborators makes the research so much more fun and so fulfilling in so many ways,” she says, “but most importantly, it benefits our patients because we can make an impact on a large scale.”

“Being at NIH has opened my eyes to so many things,” adds Dr. Chew. As her eyes continue to widen to the possibilities, it’s comforting to know she’ll be looking after ours.

Emily Chew, M.D., is a senior investigator in the Clinical Trails Branch of the National Eye Institute (NEI), where she serves as Deputy Clinical Director and Director of the Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 24, 2023