From Despair to Hope in Hours

Carlos Zarate speeds up treatment for major depression.

Carlos Zarate, M.D., develops novel medications for treatment-resistant depression and bipolar disorder

Not prone to hyperbole, Carlos Zarate, M.D., is turning pharmaceutical approaches to depression on their heads.

“We’ve got to think differently,” Zarate exclaims, describing work on the pathophysiology and treatment of major depressive disorders. “We’ve got to be game changers.”

Standard medications for life-threatening psychological illnesses usually require up to six weeks to take effect, while patients often continue to miss work and experience multiple symptoms, the most serious being suicidal ideation (the medical term for suicidal thinking).

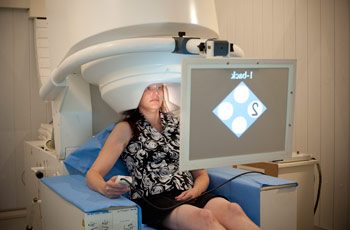

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) lab manager Judy Mitchell-Francis applies positional sensors in research

To provide better treatment results and faster symptom relief, NIH scientists needed to take a completely novel approach. But, with the neuropsychiatric marketplace seemingly awash with therapeutic options, one might imagine that most avenues for drug development in this area have already been explored.

“Over the last five decades, the drug development industry has constantly refined existing products,” Zarate says. “But what they’ve been developing is not better efficacy, but better tolerability.”

N-back testing combined with MEG allows Zarate’s team to measure brain functional connectivity as a biomarker of treatment response

Zarate and his team are pioneering the development and testing of radical new treatments for depressive illnesses, thus, taking the calls-to-action from patients and clinicians seriously.

Ketamine—a drug currently approved for the induction of anesthesia—opened a door to new possibilities and renewed hope for people living with major depressive disorders. Zarate’s experimental research in patients with refractory depression has shown unprecedented responses to ketamine within a single day and sometimes just a couple of hours.

Dr. Zarate and MEG systems analyst Frederick Carver monitor an N-back test inside the MEG unit

“Depression is a life-long illness, and the multi-episodic nature of the disease increases the likelihood of damage to critical regions of the brain that regulate emotion, cognition, and motor activity,” Zarate says. “If we can intervene very quickly and reduce the time individuals are ill, over the course of a lifetime, we can perhaps reduce the damage to the brain.”

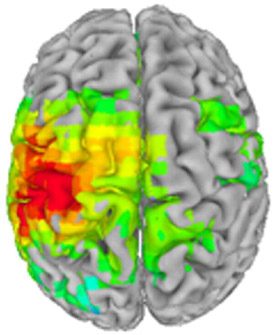

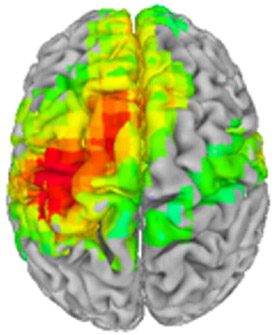

Stimulus-evoked response to stroking of the right index finger in a patient with treatment-resistant major depression, before ketamine infusion

Rapid and effective treatments may also help reduce the comorbidities associated with depression: diabetes, bone loss, and cardiovascular disease. Perhaps most importantly, Zarate’s research showed that a single intravenous infusion of ketamine reduced suicidal ideation within about an hour, and the marked improvement in symptoms was sustained over three days. From doctors’ offices to hospital emergency rooms, to battlefields around the world, ketamine and its analogs have potential to improve the quality of countless lives and save many that might otherwise be lost.

After a single infusion of ketamine, the patient’s stimulus response to finger stroking shows enhanced cortical excitability

In its current form, ketamine produces side effects that would limit its use as a standard of care, but the implications of Zarate’s findings have mobilized the scientific community to explore similar compounds with fast-acting antidepressant effects, such as ketamine-like drugs and scopolamine, a medication approved for the prevention of motion sickness. Since publishing the initial ketamine results, Zarate has received hundreds of emails each day from patients, physicians, and caregivers asking when the drug will be available. But he cautions that creating new medications takes time, and for good reasons. Unless administered in a controlled clinical environment, ketamine can result in dissociative side effects, so further research aims to identify similarly effective ketamine analogs with rapid onset and fewer deleterious side effects.

Dr. Zarate discusses depressive symptoms

Few facilities can conduct the types of research needed to demonstrate the efficacy and tolerability of experimental anti-depressive medications. One advantage of working in the NIH Clinical Center is the ability to conduct single-site, drug-free clinical trials. Studying refractory patients—of whom 60 percent have attempted suicide, most have seen little or no improvement from six or seven different antidepressant medications, and up to 60 percent have tried electroconvulsive shock therapy with no benefit—requires a specialized inpatient unit where clinical trial participants can come off any current medications in order to clearly establish efficacy for experimental trial therapies.

Producing dramatic resolution of depressive symptoms within a couple of hours—what Zarate calls “breaking the sound barrier” of psychiatric medication research—challenges scientists to uncover ketamine’s exact mechanism of action (MOA), a process perfectly suited to the hub of biomedical expertise found at the NIH Clinical Center. A ketamine MOA study was recently established to investigate what molecular pathways underlie ketamine’s dramatic effects. Genetics and proteomics, combined with multimodal state-of-the-art imaging technologies, such as PET, MRS, fMRI, 3T MRI, and 7T MRI, provide Zarate and his colleagues an in-depth biological view of the ketamine response.

The clinical team (left to right): research nurses Valerie Greene, Nancy Brutsche, and Clara Moore, and Dr. Zarate

“This hospital is quite unique in providing access to so many core facilities,” Zarate says. “There is no single person, either me or in my team, that could possibly look at all these different parameters.”

Intramural researchers now have several new trials underway, including investigations into ketamine-like drugs and delivery systems, such as intranasal sprays and transdermal patches, which may one day bring hope for a better life to people with major depressive disorders around the world.

Carlos Zarate, M.D., is Chief of the Experimental Therapeutics & Pathophysiology Branch and the Section on the Neurobiology and Treatment of Mood Disorders at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 24, 2023