The Broken Leg Mystery

Michael Collins and his Clinical Center colleagues cure a teenager of a debilitating bone disorder.

Michael Collins, M.D.

Fourteen-year-old Erin Jones first came to see Michael Collins, M.D., at the NIH Clinical Center in the summer of 2010. She had broken one leg at age 11 in a simple bike accident. A few months later, her dog jumped into her lap and the chair she was sitting in collapsed. Jones broke her other leg.

“I got out of one cast, got the flu, then got into another cast,” she said, remembering that difficult year. In addition to the big breaks, Jones had a dozen small fractures through her body, from her ribs to her feet.

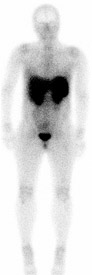

A full-body pentetreotide scan to search for tumors

Doctors suspected an underlying skeletal disorder. Jones had been developing normally, so when her blood phosphorus level came back low, they thought of tumor-induced osteomalacia, a disorder caused by a benign tumor that produces the hormone FGF23, which affects the metabolism of phosphorus and vitamin D and, ultimately, bone strength.

The disorder is very rare—there are fewer than 200 cases in the medical literature, Collins said—and exceedingly rare in children. Complicating the search for a cure for Jones was the nature of the tumors. They are typically very small and can appear anywhere from head to toe, in soft tissue or bone.

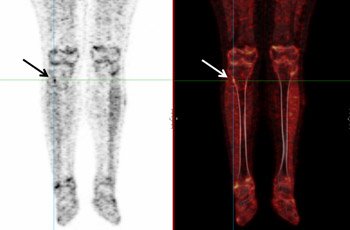

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (left) and FDG-PET/CT merged image (right) helped locate the tumor (arrow).

Her physicians in Seattle did a positron emission tomography (PET) scan and a pentetreotide scan, which looks for tumors, but couldn’t find anything. These tests are very sensitive, and in a patient like Jones with multiple fractures, they can “light up like a Christmas tree,” Collins said. Deciding which marks on the scan could be the culprit is the difficult part.

While these tumors are always hard to find, Jones’ was proving to be a particularly difficult one. Clara Chen, M.D., a nuclear medicine physician, and Andrew Dwyer, M.D., a radiologist, conducted a series of scans on Jones at the NIH, and through a painstaking process of elimination, narrowed the possible trouble spots to an area next to Jones’ right tibia.

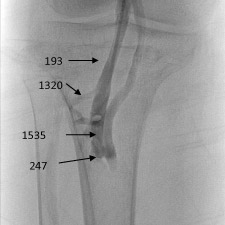

Sampling venous blood for the hormone FGF23 helped to localize the tumor.

To pinpoint the tumor, Collins recruited Richard Chang, M.D., Chief of the Endocrine and Venous Services Section in Clinical Center Radiology and Imaging Sciences Interventional Radiology Section. Chang threaded a catheter down a vein in Jones’ leg and took blood samples at different points to test the levels of FGF23. The numbers spiked around the tumor.

Jones was at her grandmother’s house when Collins called with the news. When she heard they’d found the tumor, she gave her grandmother a thumbs up. “She started screaming, she was so happy,” Jones remembered.

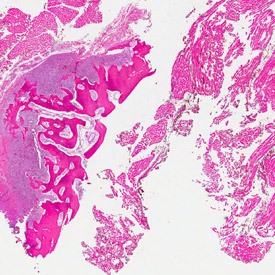

Slices through the tumor excised from Jones’ leg

Felasfa Wodajo, M.D., Medical Director of Inova Health System’s Musculoskeletal Tumor Program and a consultant to the National Cancer Institute, removed the tumor in August. Recurrence is rare, especially when a large margin of surrounding tissue is removed, as was done with Jones.

Jones is back in Washington, returning to life as a healthy teen. “I’m back on my swim team, which I really love,” she said. “I can walk in the hall without being worried about knocking into something.”

With her disorder cured, Erin Jones returned to the swim team.

The end result wasn’t due to fancy science, Collins said, just meticulous, rigorous teamwork with Clinical Center colleagues.

“How often in medicine do you get a chance to really cure someone? That was fantastic.”

Michael Collins, M.D., is Head of the Skeletal Clinical Studies Section of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

Adapted from an article that appeared in Clinical Center News, October 2010

This page was last updated on Monday, July 1, 2024