A Broken Link in the Chain

Janet Hall explores the cascading effects of hormonal disruptions on the reproductive system.

As the NIEHS Clinical Director, Dr. Janet Hall (right) works closely with Dr. Stavros Garantziotis, Medical Director for the NIEHS Clinical Research Unit.

Scientists commonly compare the human brain to a computer and the body to a machine, but when it comes to endocrinology — the study of the body’s diverse array of hormones — Janet Hall, M.D., M.S., makes the body sound more like a crowded table at a dinner party.

“There’s a tremendous amount of cross-talk,” says Dr. Hall, Clinical Director at the NIH National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and head of its Reproductive Physiology and Pathophysiology Group. “Endocrinology really is about how the body stays in sync and how it reaches a kind of homeostasis by having various parts of the body talk back and forth to each other.”

Unfortunately, as anyone who has played the game of telephone knows, an error early on in the chain of communication can dramatically alter the end result. Dr. Hall specifically investigates what happens when the hormonal processes that govern reproduction go haywire: infertility, irregular menstrual cycles, or the complete absence of periods. In her efforts to learn more about reproductive endocrine disorders, Dr. Hall begins at the top and works her way down.

“Most people think about the reproductive system as all about the gonads and about estrogen and testosterone, but in fact the reproductive system is entirely dependent on what happens in the brain,” she explains.

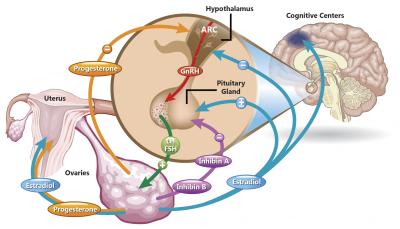

A complex chain of events that begins in the brain controls reproductive function. A problem with any one part of this system can cause a wide array of symptoms, including infertility or a halt in a woman’s menstrual cycle.

One of the primary drivers of reproductive function is a set of neurons in a brain region called the hypothalamus. These cells secrete a hormone called gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which travels to the body’s pituitary gland and causes it, in turn, to release luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) into the bloodstream. In women, these two chemicals tell the ovaries to release the hormones estradiol and progesterone, which are responsible for creating the gender-specific characteristics girls develop when they enter puberty, as well as controlling the menstrual cycle. To make matters even more complicated, estradiol from the ovaries travels back up to the hypothalamus and curbs the release of GnRH.

Dr. Hall has spent much of her career studying GnRH deficiency, attempting to understand the genetic factors that contribute to it and treating patients who never enter puberty and are infertile because their GnRH neurons do not work properly. Research she contributed to early in her career helped bring about the FDA approval of GnRH treatments for this patient population. Restoring normal levels of GnRH has cascading, corrective effects all the way down the hormonal chain. Dr. Hall’s efforts to restore fertility in women who had been told they would never have children have had a particularly profound effect on her.

Dr. Hall’s research uses a wide array of equipment to examine how lifestyle factors influence reproductive function. This ‘Bod Pod’ measures the ratio of body fat to lean tissue like bone and muscle in a person’s body.

“I have patients whose children are now in their twenties and I still get cards from them every year letting me know how their kids are doing,” Dr. Hall says. “It’s pretty exciting and pretty fulfilling.”

Of course, as a researcher at an institution with the word ‘environmental’ in its name, Dr. Hall’s work also explores how environmental and lifestyle factors like diet and exercise affect reproductive function. One of her lab’s current projects focuses on women with a condition called hypothalamic amenorrhea, in which the body responds to weight loss by curbing GnRH production, thereby shutting down the menstrual cycle. However, not all women’s bodies react this way, and Dr. Hall wants to understand why.

“There are some women who are incredibly tolerant to exercising and losing weight and there are other women who stop cycling with very minimal decrease in energy intake or increase in exercise,” Dr. Hall explained.

Dr. Garantziotis examines a patient visiting the Clinical Research Unit.

By studying genes involved in GnRH regulation and comparing how different women’s hormone levels change in response to a reduced calorie intake, Dr. Hall hopes to one day be able to predict individuals’ susceptibilities to developing hypothalamic amenorrhea. This sort of work requires a flexibility that Dr. Hall views as a key component of the NIH’s Intramural Research Program.

“One of the things that is particularly helpful is the freedom to be more nimble in the research that we do, to be able to follow leads, and to be able to take risks,” Dr. Hall says. “These opportunities can really drive the field forward and are an incredibly important part of what the intramural program offers.”

Janet Hall, M.D., M.S., is the Clinical Director at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the head of its Reproductive Physiology & Pathophysiology Group.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 24, 2023