‘Sticky’ gene may help Valium calm nerves

IRP mouse study could prompt scientists to rethink how benzodiazepines work

Between 1999 and 2017, the United States experienced a 10-fold increase in the number of people who died from overdoses of Valium and other benzodiazepines. For years, scientists thought that these powerful sedatives, which are used to treat anxiety, muscle spasms, and sleeping disorders, worked alone to calm nerves. Now, in an article published in Science, researchers from the National Institutes of Health show that this view of the drugs and the neural circuits they affect may have to change. In a study of mice, scientists discovered that both may need the assistance of a ‘sticky’ gene, named after a mythological figure, called Shisa7.

“We found that Shisa7 plays a critical role in the regulation of inhibitory neural circuits and the sedative effects some benzodiazepines have on circuit activity,” said Wei Lu, Ph.D., a Stadtman Investigator at NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the senior author of the study. “We hope the results will help researchers design more effective treatments for a variety of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders that are caused by problems with these circuits.”

Dr. Lu’s lab studies the genes and molecules used to control synapses; the trillions of communications points made between neurons throughout the nervous system. In this study, his team worked with researchers led by Chris J. McBain, Ph.D., senior investigator at NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), to look at synapses that rely on the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) to calm nerves. Communication at these synapses happens when one neuron fires off packets of GABA molecules that are then quickly detected by proteins called GABA type A (GABAA) receptors on neighboring neurons.

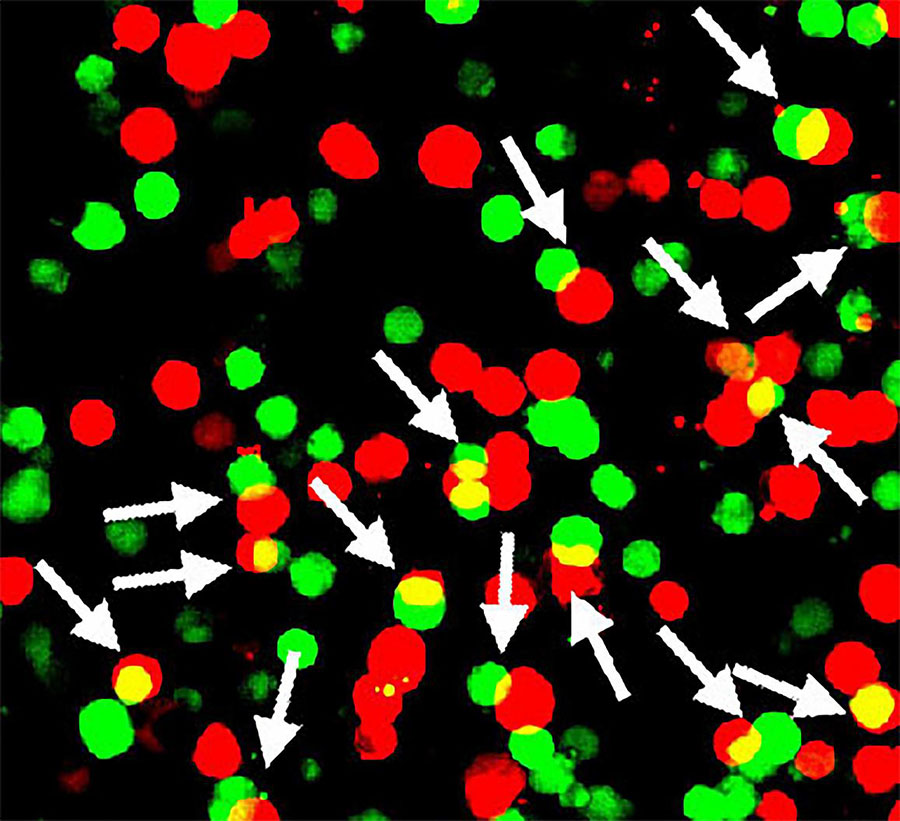

In a study of mice, NIH researchers showed that a protein encoded by a gene called Shisa7 (green) may boost the nerve calming effects of valium and other benzodiazepines by sticking to GABA type A neurotransmitter receptors (red).

This page was last updated on Friday, January 21, 2022