Novel imaging approach reveals important details about rare eye disease choroideremia

New findings could improve the development and efficacy of therapies

By combining traditional eye imaging techniques with adaptive optics — a technology that enhances imaging resolution — researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI) have shown for the first time how cells across different tissue layers in the eye are affected in people with choroideremia, a rare genetic disorder that leads to blindness. Their study, which was funded by the NEI Intramural Research Program, is published in Communications Biology. NEI is part of the National Institutes of Health.

Johnny Tam, Ph.D., head of the NEI Clinical and Translational Imaging Unit combined adaptive optics with indocyanine green dye to view live cells in the retina, including light-sensing photoreceptors, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and choroidal blood vessels. His team was able to see in detail the extent to which choroideremia disrupts these tissues, providing information that could help design effective treatments for this and other diseases. The retina’s RPE is a layer of pigmented cells essential to the nourishment and survival of photoreceptors.

Choroideremia affects men more than women because the gene responsible for the disease is located on the X chromosome. Since men have only one copy of the X chromosome, a mutation in the gene causes males to develop more severe symptoms, while females — who have two copies of the X chromosome — usually have milder symptoms, having one working copy of the gene on the other X chromosome.

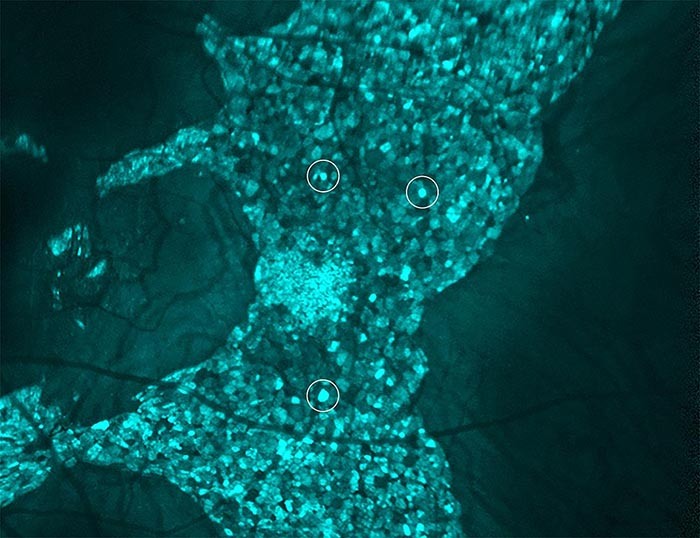

“One major finding of our study was that the RPE cells are dramatically enlarged in males and females with choroideremia,” said Tam. “We were surprised to see many cells enlarged by as much as five-fold.”

RPE cells (see circled examples) in a male participant with choroideremia, showing that enlarged RPE cells can be detected using Dr. Tam’s multimodal imaging approach.

This page was last updated on Monday, October 10, 2022