NIH scientists and collaborators find infectious prion protein in skin of CJD patients

National Institutes of Health scientists and collaborators at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, have detected abnormal prion protein in the skin of nearly two dozen people who died from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). The scientists also exposed a dozen healthy mice to skin extracts from two of the CJD patients, and all developed prion disease. The study results, published in Science Translational Medicine, raise questions about the possible transmissibility of prion diseases via medical procedures involving skin, and whether skin samples might be used to detect prion disease. Researchers from NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) were co-leaders of the study, which included multiple collaborating groups. They stress that the prion-seeding potential found in skin tissue is significantly less than what they have found in studies using brain tissue.

CJD is an incurable — and ultimately fatal — transmissible, neurodegenerative disorder in the family of prion diseases. Prion diseases originate when normally harmless prion protein molecules become abnormal and gather in clusters and filaments in the human body and brain. The reasons for this process are not fully understood. The accumulation of these clusters has been associated with tissue damage that leaves sponge-like holes in the brain. Human prion diseases include fatal insomnia; kuru; Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome; and variant, familial and sporadic CJD. Sporadic CJD is the most common human prion disease, affecting about one in one million people annually worldwide. Other prion diseases include scrapie in sheep; chronic wasting disease in deer, elk and moose; and bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or mad cow disease, in cattle.

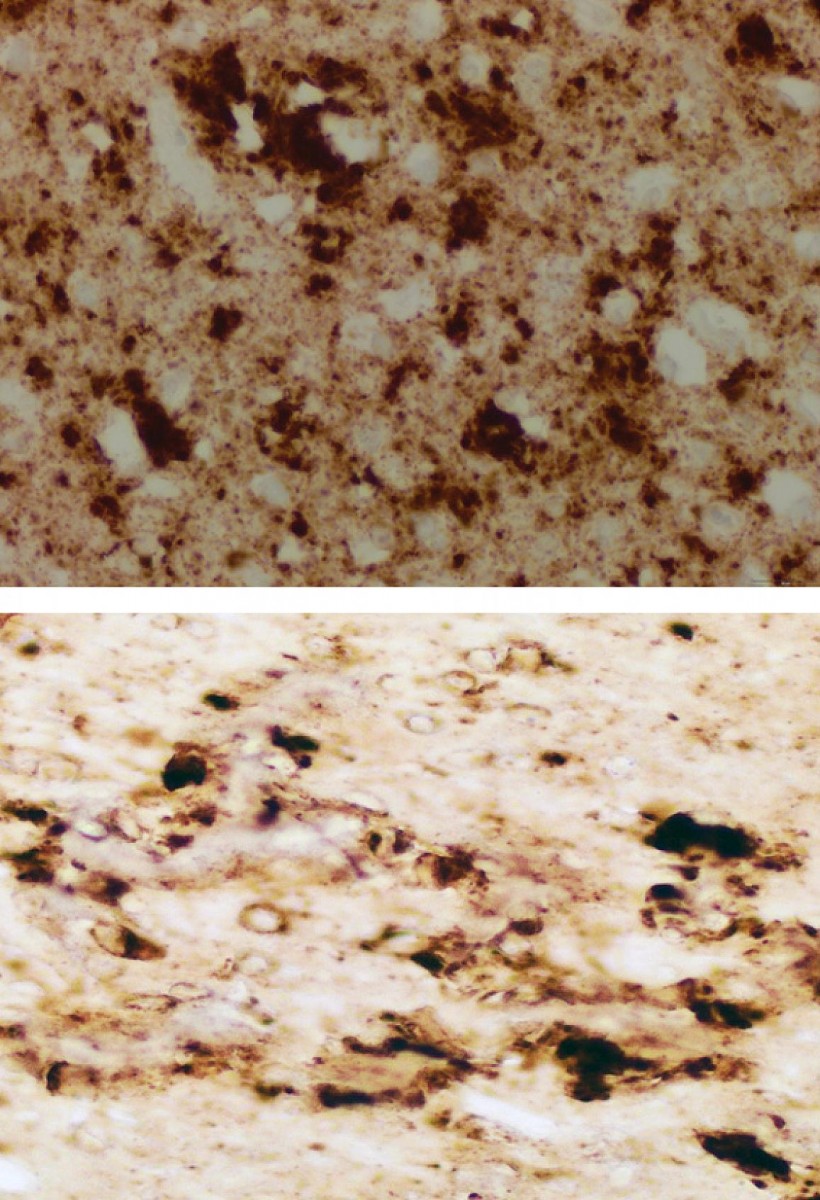

The brain of one patient who died from sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease (sCJD) appears nearly identical to the brain of a mouse inoculated with infectious prions taken from the skin of patients who died from sCJD.

This page was last updated on Friday, January 21, 2022