Meningitis changes immune cell makeup in the mouse brain lining

NIH study finds new cell composition may lead to less effective future response

Meningitis, a group of serious diseases which infect the brain’s lining, leaves its mark and can affect the body’s ability to fight such infections in the future. According to a new study published in Nature Immunology, infections can have long-lasting effects on a population of meningeal immune cells, replacing them with cells from outside the meninges that then change and become less likely to recognize and ward off future attacks. The research was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), part of the National Institutes of Health.

“After an infection, the immune cell landscape in the brain lining changes. Brain lining immune cells that normally protect the brain from foreign invaders die and are replaced by cells from elsewhere in the body. These new cells are altered in a way that affects how they respond to subsequent challenges and new infections,” said Dorian McGavern, Ph.D., NINDS scientist and senior author of the study.

Using real time imaging, Dr. McGavern and his colleagues took a detailed look at mouse meningeal macrophages, which are immune cells that live in the meninges, the protective layers covering the brain and spinal cord. One group of these macrophages is found along blood vessels in the dura mater (the outermost layer of the meninges) and helps catch pathogens from the blood before they reach brain tissue. Blood vessels in the dura mater are relatively open compared to the tightly sealed vessels found in other brain regions, and macrophages in the dura mater often serve as the first line of defense against harmful blood-borne agents.

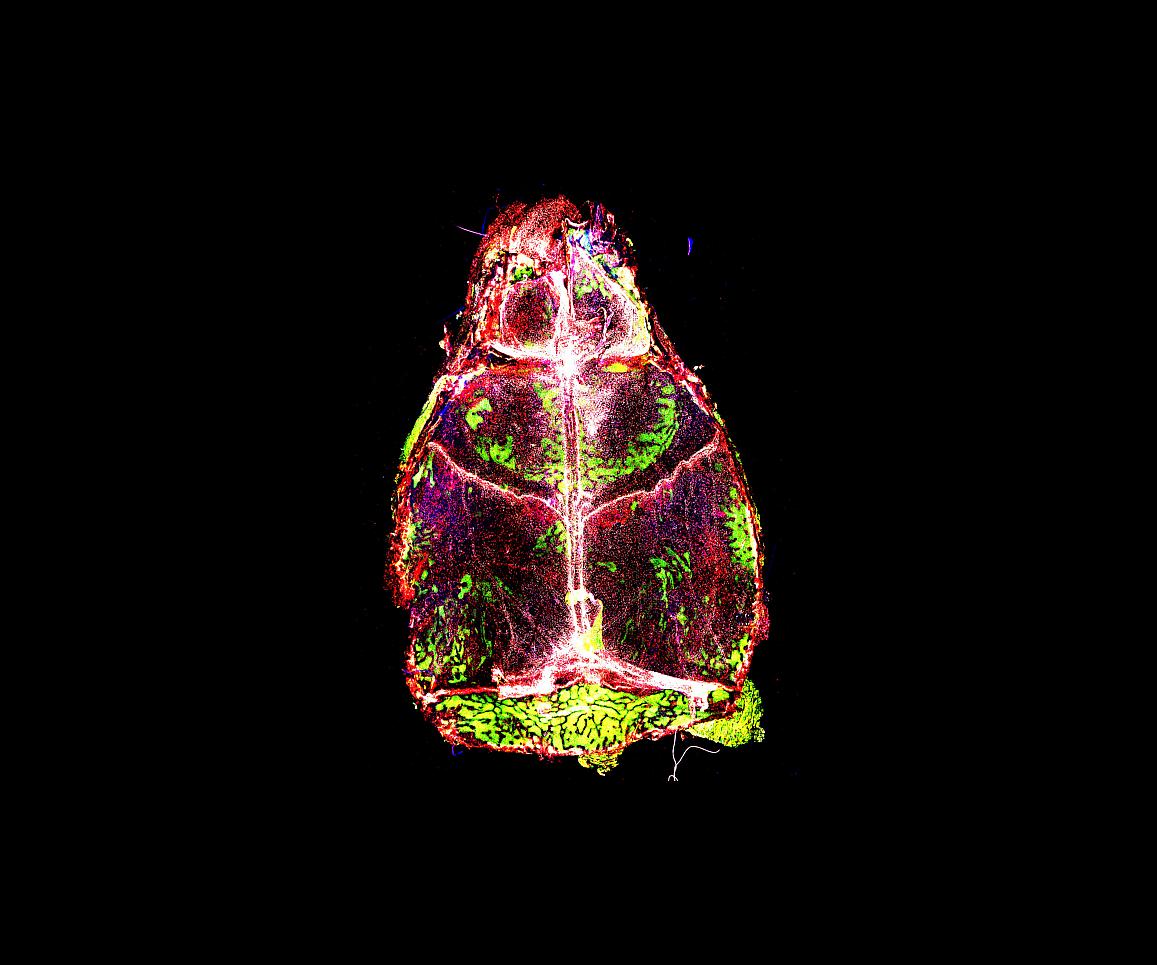

Meningeal macrophages (shown in white, red, and blue) are on constant alert against potential threats to brain tissue.

This page was last updated on Friday, January 21, 2022