IRP study shows genomic variation causing common autoinflammatory disease may increase resilience to bubonic plague

Genomic variants that cause common periodic fever have spread in Mediterranean populations over centuries, potentially protecting people from the plague

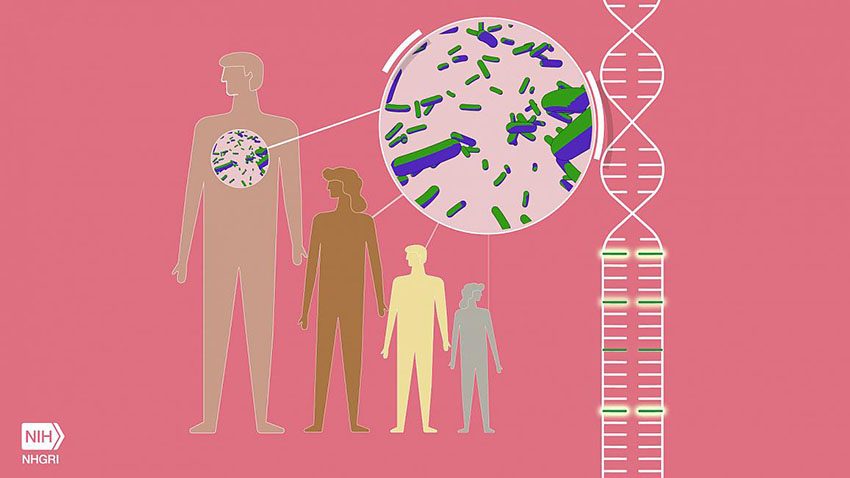

Researchers have discovered that Mediterranean populations may be more susceptible to an autoinflammatory disease because of evolutionary pressure to survive the bubonic plague. The study, carried out by scientists at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of the National Institutes of Health, determined that specific genomic variants that cause a disease called familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) may also confer increased resilience to the plague.

The researchers suggest that because of this potential advantage, FMF-causing genomic variants have been positively selected for in Mediterranean populations over centuries. The findings were published in the journal Nature Immunology.

Over centuries, a biological arms race has been fought between humans and microbial pathogens. This evolutionary battle is between the human immune system and microorganisms trying to invade our bodies. Microbes affect the human genome in many ways. For example, they can influence some of the genomic variation that accumulates in human populations over time.

"In this era of a new pandemic, understanding the interplay between microbes and humans is ever critical," said Dr. Dan Kastner, NHGRI scientific director and a co-author on the paper. “We can witness evolution playing out before our very eyes.”

Specific genomic variants that cause a disease called familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) may also confer increased resilience to the plague. Image credit: Ernesto Del Aguila III, NHGRI

This page was last updated on Friday, January 21, 2022