IRP investigators hope CD47 study leads to broad-spectrum infectious diseases immunotherapy

National Institutes of Health investigators and colleagues have discovered that when the immune system first responds to infectious agents such as viruses or bacteria, a natural brake on the response prevents overactivation. Their new study in mBio describes this brake and the way pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, turn it on. Their finding provides a potential target for an immunotherapy that might be applied to a wide range of infectious diseases.

When a cell senses an infectious agent with molecules called pathogen recognition receptors, part of its response is to increase cell surface expression of a molecule called CD47, otherwise known as the “don’t eat me” signal. Increased CD47 expression dampens the ability of cells called macrophages, the immune system’s first responders, to engulf infected cells and further stimulate the immune response. Upregulation of CD47 on cells was observed for diverse types of infections including those caused by mouse retroviruses, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, LaCrosse virus, SARS CoV-2, and by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi and Salmonella enterica typhi.

By blocking CD47-mediated signaling with antibodies in mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, the authors demonstrated they could enhance the speed of pathogen clearance. Furthermore, knocking out the CD47 gene in mice improved their ability to control M. tuberculosis infections and significantly prolonged their survival. In addition, retrospective studies of cells and plasma from people infected with hepatitis C virus indicated that humans also upregulate CD47. In these studies, inflammatory cytokine stimuli and direct infection both promoted increased CD47 expression.

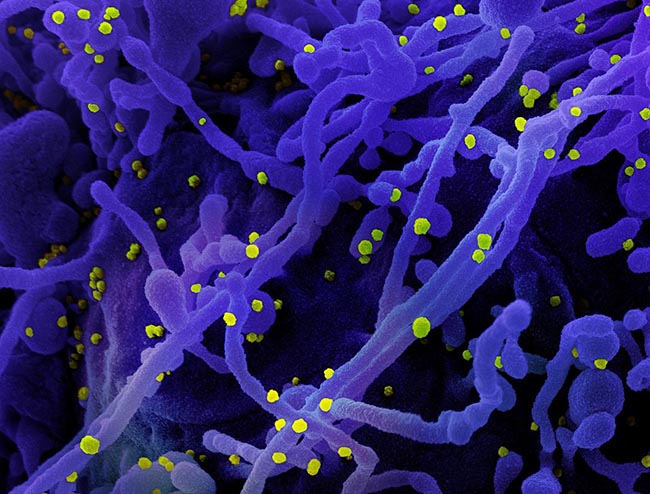

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a cell (purple) infected with SARS-COV-2 virus particles (yellow), isolated from a patient sample.

This page was last updated on Friday, January 21, 2022